My book Queer Trades, Sex & Society: Male Prostitution and the War on Homosexuality in Interwar Scotland is out now. This is a little taster.

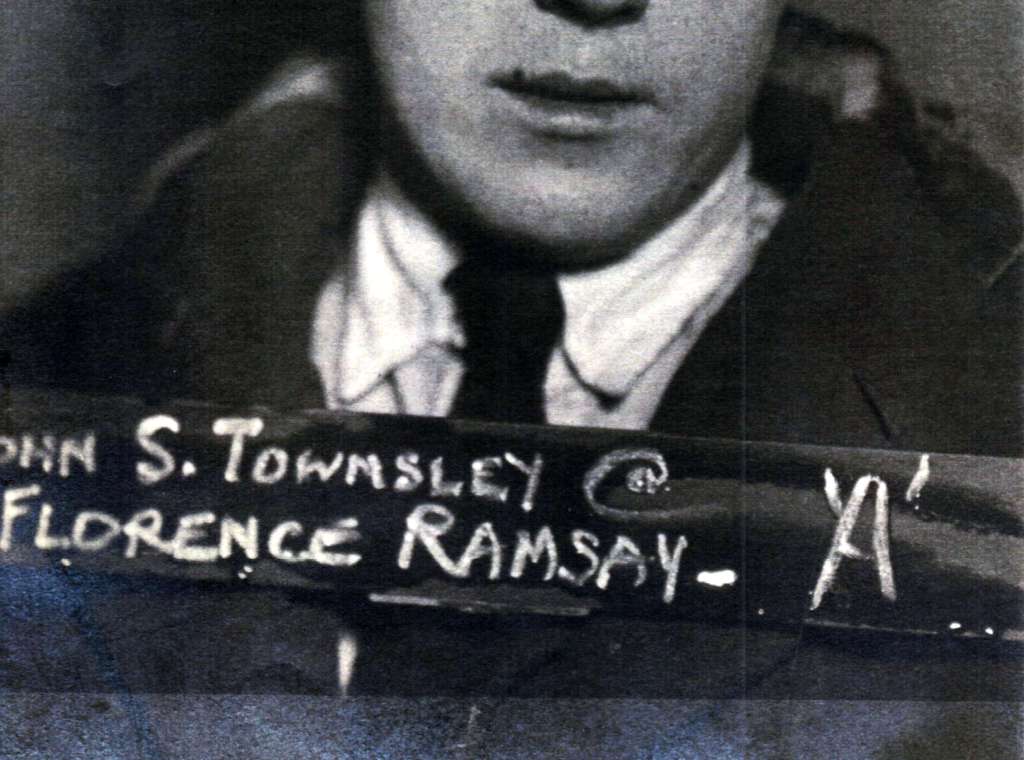

I first encountered the Whitehats in Angus McLaren’s Sexual Blackmail, almost 20 years ago. He noted that the group had caused some anxiety in Glasgow and had exercised local MP George Buchanan. As I was, at the time, undertaking oral history interviews with gay and bisexual men for my PhD, I put the Whitehats to the side. That was until I met Andrew Davies at a conference in St Andrews. I had given a paper in which I had briefly mentioned the Whitehats and he pointed me in the direction of Glasgow police archives. I had already uncovered a trial record for the ‘leader’ of the Whitehats, William Patton or Paton, but at the Glasgow archives, I was able to put a face to the name. Also there, were police records for the other members of the gang, a group of stoney-faced men in their twenties, images that contrasted with their descriptions in the press and trial records. Perhaps ‘stylishly-dressed’ and ‘fashionably-dressed’ looked different then. That is, compared to William Paton (aka Liz Paton), with his wing collars, thin tie and baker’s boy flat cap. But I did not know quite how to categorise men such as Paton, John Townsley (aka Florence Ramsay), Thomas Robb (aka Maria Santoye), Patrick Neville (aka Ella Shields), Joseph McMahon (aka Happy Fanny Fields) ,and the others. While their working or camp names (and their use of ‘powder and paint’) expressed a level of femininity or queerness – and some of them had convictions for homosexual ‘offences’ – most had convictions for other crimes; theft, robbery, violence, and sexual assault. Buchanan had also suggested that the group engaged in (homo)sexual blackmail but had not been prosecuted due to the victim’s unwillingness to appear in court. But this was a group identified by the police and courts as a ‘gang composed of male prostitutes’.

The more I dug, the murkier it became. Paton’s ’empire’ had begun with organising illegal nightclubs and female prostitution in the West End of Glasgow (one being above The Arlington Pub ). Paton would rent premises by presenting himself under a pseudonym, with a ‘fake’ wife (generally one of the sex workers) to the letting agencies, sometimes calling himself William Dallas or Greig or Robertson. Once the premises were secured and furnished with a full bar, and some ladies, Paton and his associates would stake out the main railway stations seeking male visitors to the city, who they entice back to the premises with promises of cheap drink and sex. Once the operation was smashed by the police, Paton would be described in the press as the leader of the underworld of Glasgow (something of an exaggeration) and ‘the dynamic force among a number of notorious men and women of fashionable appearance’. Paton got 18 months. That 18 months added to his considerable criminal record. Paton was by then 31 years of age and he already held a number of convictions in Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow. As did his mother Agnes. Agnes ran the ‘legitimate’ side of their enterprise, first a cafe in Stobcross Street and then a fish restaurant on the Broomielaw. The rear living quarters of the restaurant would act as a brothel for male sex work.

Paton was released early from his sentence suffering from colo-rectal cancer. He survived. But his influence and desire had diminished. The restaurant on the Broomielaw was not proving to be a success, so Paton returned to queer male sex work (actually where his criminal career in Glasgow had begun). The restaurant acted as a form of hub for the Whitehats, as the cafe in Stobcross Street had previously. But by now, Paton was a marked man, followed by the police wherever he went. And on one evening in September 1928, it all came to an end. After escorting a soldier back to the Broomielaw ‘brothel’, Paton was caught in the act, thanks to an electric lightbulb, an uncurtained window and a nephew suffering from encephalitis lethargica – the uncurtained window and lightbulb presented the police with a perfect view, and the nephew asleep in the same room, made the act ‘public’. Paton got 3 years. Some of the Whitehats had died while Paton was in prison, others had returned to ‘normal’ trades (some were married with children), while others like John Townsley drifted into petty criminality and alcoholism (he was prosecuted at least once every year between 1926 and 1937 for either theft or assault). The Whitehats may have offered some of these men regular income but perhaps without Paton, the group disintegrated. Agnes held on for couple of years until the restaurant failed and became dependent on poor relief, as did WiIliam on his release from prison. In one application Agnes states that none of her other 5 children were willling or able to assist.

While it is possible to admire some of Paton’s brashness (such as ‘dragging up’ as a Spanish cabaret artiste to fraudulently collect donations for a charity – it was a fancy dress event), he and his confederates engaged in a range of criminal activities. They might well have been ‘queer’ but they posed a threat to to other queer men through blackmail and harrassment. Paton cared for his ageing mother until her death in 1943, aged 90. He then moved to Edinburgh where he worked in a number of hotels including the North British Hotel (now The Balmoral), flirted with marriage, before ending his days living in Stockbridge with his male ‘intimate partner’. He died from heart failure in 1968. The story of the Whitehats offers one interpretation or insight into queer male prostition/sex work. The story of the Rosebery Boys in Edinburgh in the 1930s offers another; a much more human and personal insight into queer male identity and sex work. And you can read more in Queer Trades, Sex & Society. But I will leave you with an extract from a letter from one Rosebery Boy to another.

Well Princes [sic] I met a swell sheik on Sat. and I am madly in love with him. Honest M. I love that chap the way I’ve loved no one else. Gee he is a swell guy. I have been crying all day when I think of the way he was smiling last night […] I told him on Sat. that I loved him and I told him last night […] I give up the game for good. I will camp to men but I won’t go with them. I am serious M., if I can’t get him I don’t want anyone else; he is everything to me.

Congratulations.

LikeLiked by 1 person