Scotland’s Queer Heritage

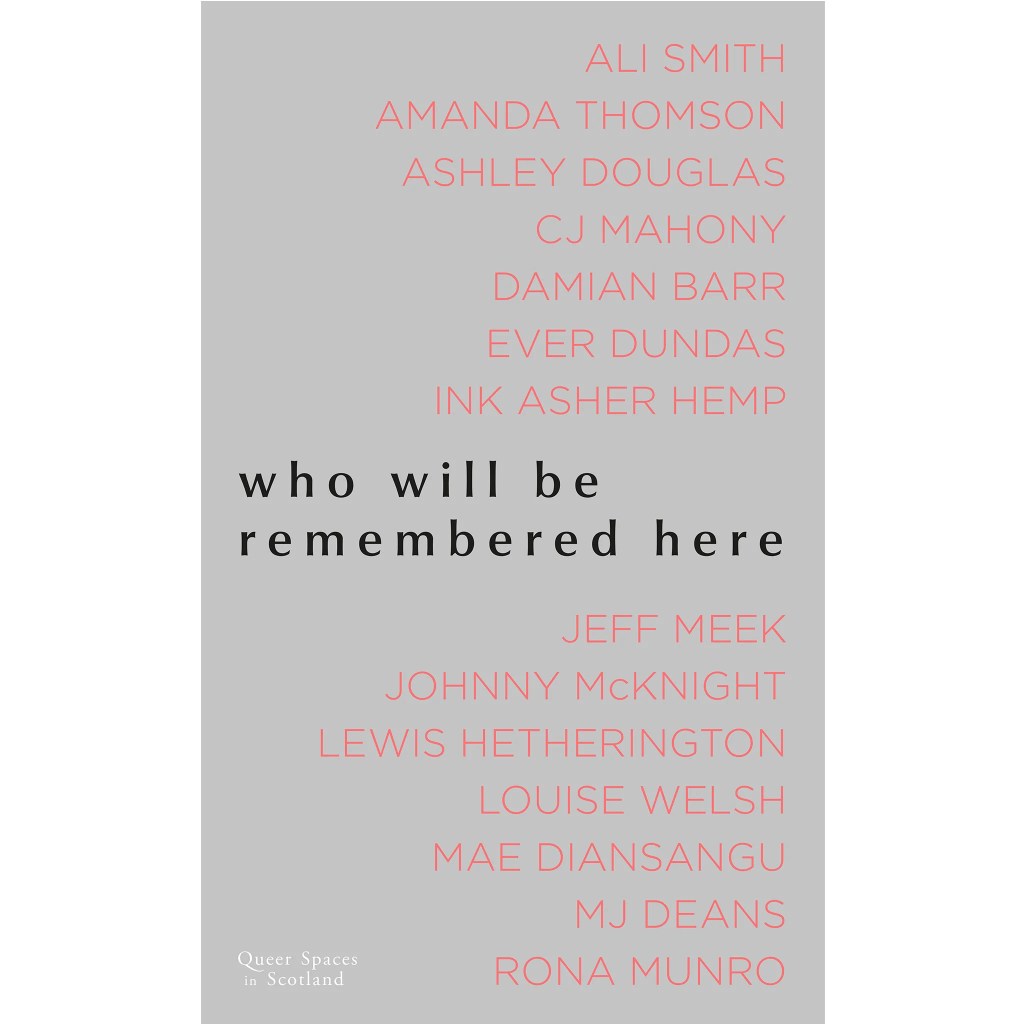

Exploring environments across Scotland, 14 writers share the places and spaces which define their queer history.

who will be remembered here reconsiders and reimagines the built and natural environment through a queer lens, uncovering stories full of hope and humanity, and the collection features images from HES archive.

Contributors are Ali Smith, Damian Barr, Ink Asher Hemp, Mae Diansangu, Ashley Douglas, Amanda Thomson, Jeff Meek, Rona Munro, MJ Deans, Louise Welsh, Ever Dundas and Johnny McKnight, along with Lewis Hetherington and CJ Mahony who are also the book’s curators. The book features works in English, Scots and Gaelic.

2025 marks a significant point in LGBTQ history, being 30 years since the first major Pride event in Scotland. Queer history is an important part of Scotland’s past, but it is largely absent from records. By making invisible stories visible, who will be remembered here ‘captures something of the richness, complexity and beauty of a history that belongs to all of us’.

The book will be released in the 14 of August and can be pre-ordered.

Pride: The books that shaped us

This year the National Library of Scotland is 100 years old and we asked people to share the books they love with us. To mark Pride, our panel of LGBT+ individuals will talk about the books and publications that have influenced their lives.

Panellists

Sasha De Buyl (Chair) is a writer and programmer from Cork. Their work has been published in ‘Gutter’ and ‘The Stinging Fly’ among others. and They are currently undertaking a DFA in Writing at the University of Glasgow.

Graeme Hawley (Head of Published Collections at National Library of Scotland) works at the Library and is used to dealing with millions of books. But out of that huge collection some are more personally significant than others. He shares the books that were helpful to him in his coming out, and a tiny entry in ‘The List’ with a big memory attached to it.

Sigrid Nielsen co-founded Lavender Menace, Scotland’s first lesbian and gay community bookshop, as a partnership in 1982. Sigrid managed author readings, mail order lists, and bookshop events. She left as a partner in 1987 and later co-edited ‘In Other Words: Writing as a Feminist’ (Hutchinson Education, 1987) and published articles and short stories. In 2019, she and Bob revived Lavender Menace as an LGBT+ books archive and heritage organisation.

Other panellists to be announced.

Our audience will also be invited to share memories and recommendations of books that have influenced them.

This event has been developed in partnership with Lavender Menace and will be highlighting their queer books archive.

This event has been programmed as part of WestFest – Glasgow’s biggest cultural and community festival.

Our Myriad lgbtqi+ Lives

3pm, Wednesday 12th February, Dalhousie 2F11

Speaker, Brian Dempsey, School of Law

All welcome, registration required. Please visit here to register.

We have always been part of Scottish history, and we continue to make Scottish history.

- From the 6th century man-loving priest Findchän to the unnamed trans or intersex person (‘skartht’) whose very existence was supposedly a portent of James II’s death (1460)

- via the ‘female sodomites’ Elspeth Faulds and Margaret Armour (1625), the ‘lesbian schoolmistresses’ Jane Pirie and Marianne Woods (1810) and the gender fluid paganist William Sharpe/Fiona Macleod (d. 1905)

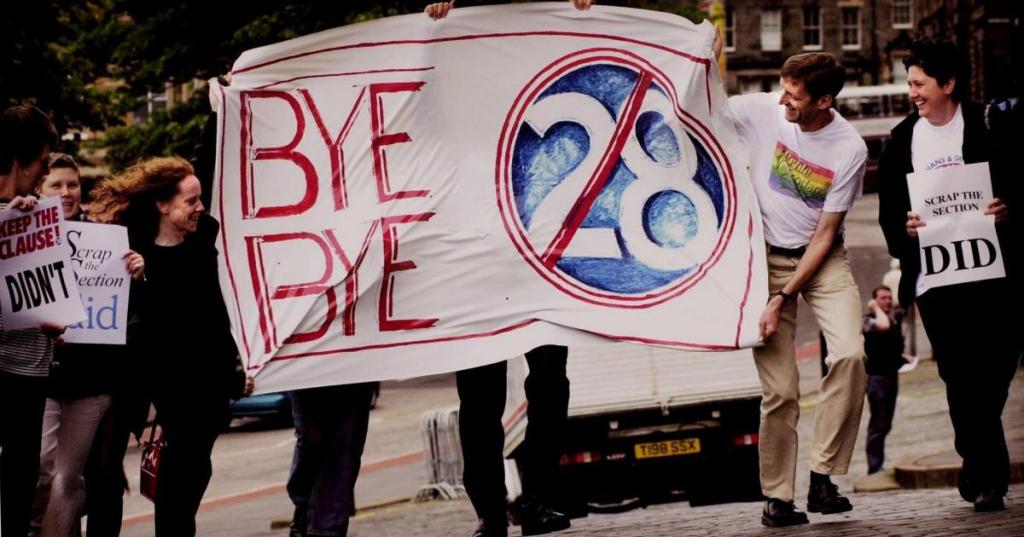

- to the fight for repeal of ‘Section 28’ (2000), for marriage rights (2014) and for respect for trans autonomy (ongoing) and infinitely more.

Let’s share and celebrate some of Scotland’s many lgbtqi+ lives.

Homosexuality and the Scottish Press 1880-1930

A guest post by Dr Michael Shaw, Senior Lecturer in English Studies at the University of Stirling.

In his History of Sexuality, Michel Foucault famously critiqued the ‘repressive hypothesis’. Far from simply being repressed or restricted over the nineteenth to twentieth centuries, Foucault argued that there was a proliferation of discussion on sexuality at this time, an ‘incitement to speak about it’. I’ve often wondered about how this idea might apply to Scotland, which is sometimes portrayed as a nation that was either silent or quiet on homosexuality before the 1960s. How extensively would homosexuality have been discussed in Scotland between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, and in what contexts? How would it have been alluded to? Was the treatment always hostile? And what materials might still exist to help us understand these discourses today?

Over the past year I’ve been working on a Royal Society of Edinburgh-funded project, titled ‘Homosexuality and the Scottish Periodical Press 1885-1928’, to address the above and related questions. Having done some initial research on the representation of the Oscar Wilde trials in the Scottish press, and knowing how extensively his trials were covered in some Scottish newspapers, I wanted to think more broadly about the ways in which Scottish print culture engaged with homosexuality, beyond criminal trials and police reports. How might queer novels, or sexological writings, have been received in Scotland, for instance? Were poems or stories alluding to same-sex love published in the Scottish press?

I knew I would likely have to confront a range of ‘negative results’ during this project: there would undoubtedly be newspapers and magazines that enforced a studied silence on homosexuality. Those silences themselves are of interest, but I suspected that there would also be more coverage of homosexuality, beyond criminal cases, than tends to be acknowledged.

The project took me to various locations, ranging from Dumfries to Dingwall. Rather than rely on electronic databases, I wanted to work with physical collections as much as possible – making sure that lesser-known titles were consulted as much as the more obvious newspapers and magazines. Given the vibrancy of Scottish periodical culture c.1880-1930, I knew there was no way I could be exhaustive with this study. But I wanted to build a thorough sample, by exploring how periodicals from different locations, with differing political persuasions and religious associations, speaking to different professions or groups, discussed (or didn’t discuss) homosexuality.

What became clear was that there were a number of discussions of, and allusions to, homosexuality in Scotland over this period in the press, although there were differences in the way the topic was handled across different years and locations. It also became clear that discussion of homosexuality and homosexuals was not always hostile (future publications will discuss these findings in more detail).

Sometimes, it was in seemingly unlikely places that expressions of sympathy were found. The Scots Observer (1926-34), for instance, was a weekly newspaper devoted to representing the presbyterian churches of Scotland, hoping to express ‘the collective aims and ideas of the Scottish Presbyterian Churches’. The Scots Observer was also concerned with the Scottish literary renaissance and intellectual developments of the day, and it did not always manage to reconcile its differing concerns. The editor, William Power – who was not only a supporter of the Renaissance, but would go on to become the leader of the Scottish National Party during the Second World War – later noted that the political and intellectual sympathies of the paper drew critique from some of the church leaders.

The Scots Observer’s more provocative dimensions are evident in an anonymous 1927 review of a book titled The Invert and his Social Adjustment by ‘Anomaly’ (who describes himself in the book as a Roman Catholic, aged 40). The review not only discusses homosexuality but calls for greater tolerance of homosexuals:

Of recent years it has been found that a certain proportion of people […] are as instinctively homosexual as the normal individual is heterosexual. […] Such people have special and very difficult problems in life to face, and an idea of what these are and how they may be faced is given in a recently published book “The Invert and His Social Adjustment’. […] The writer, who is himself an invert, and also a devout Roman Catholic, makes it clear that the incidence of immorality among inverts is precisely the same as among normal people, and he also shows how, in the necessary process of “sublimation,” socially valuable qualities may be developed.

Much like the book, homosexuality is represented as ‘abnormal’ here but it is simultaneously characterised as being as ‘instinctive’ as heterosexuality, and the review highlights the difficulties homosexuals in the early twentieth century had to face. The reviewer also appears to be convinced by the author’s dissociation of homosexuality from immorality. Following these comments, a quote is included from the ‘wisely written’ introduction to the book by Dr Robert H Thouless, a Lecturer in Psychology at the University of Glasgow at that time. Thouless stated that the book helps to ‘approach the problems of inversion with knowledge and charity’, which is the note the review ends on. In his introduction, Thouless also noted that ‘the virtuous love of a homosexual is as clean, as decent, and as beautiful a thing as the virtuous love of one normally sexed’.

The Scots Observer’s review does stress the ‘necessary’ process of sublimation (deflecting sexual thoughts towards non-sexual activities), which appears to depart from the book’s ambivalence around physical intimacy: ‘Anomaly’ focuses on challenging ‘excessive indulgence’, while noting that homosexual love is ‘no more susceptible to sublimation into an absolutely non-physical emotion than the love of man for a woman’. While there is no negative commentary on the ideas voiced in The Invert and his Social Adjustment, The Scots Observer does appear to take a more conservative stance on physical intimacy in its review.

Nevertheless, in choosing to give notice to this book, and in sympathising with its calls for greater toleration of homosexuals, we witness an example of the ways in which Scottish newspapers and magazines, including religious titles, could contribute to expanding awareness of homosexuality in the 1920s, even if – going back to Power – this may have been one of the contributions that certain church leaders disapproved of. It is clear that Scottish periodicals were not always concerned with repressing discourse around homosexuality; not uncommonly, they were sites to discuss, analyse, condemn and sympathise with homosexuals across the 1885-1928 period.

If you would like to provide a guest article for QueerScotland, please do get in touch.

Fear, Shame and Hope: AIDS in 80s and 90s Scotland

In a recent blogpost John D’Emilio argued that AIDS and its impact upon LGBT individuals and organisations, the militancy it provoked, and the heightened attention it drew to LGBT causes needs to be more fully documented and appreciated. This is certainly applicable to Scotland, and its responses, both social and medical, to the significant challenges that HIV/AIDS brought.

My research engaged with the impact that HIV/AIDS had upon gay and bisexual men in Scotland, many of whom were relatively young when their lives were touched or influenced by this new and sinister threat to life. Scotland had only decriminalised consensual gay sex between male adults in 1980, and the drive for equality was realistically still in its infancy. This blog post is not an attempt to document Scottish responses to HIV and AIDS but to reflect the experiences of gay and bisexual men during the 1980s and 1990s.

Chris was in his early 20s when the HIV/AIDS ‘dark cloud’ settled over Scotland:

It was horrendous, absolutely horrendous. Fear, fear of something you had taken for granted that was a big part of your identity and how you find joy and happiness and intimacy with other people that could suddenly wipe you out and do it horribly, you know, horribly…it was specifically, gay men who were isolated at that time, so there was another bit of ammunition for people who had a big grudge against gay men or didn’t like homosexuality for whatever reason, there was another huge big bit of ammunition.

Although the majority of early HIV/AIDS cases in Scotland affected another marginalised group – intravenous drug users, especially in Edinburgh – it was not long before the illnesses began to affect Chris much more directly. The impact was felt on a personal and emotional level, but also in the way that gay men saw themselves and were seen by wider society:

JM – Would you say that it impacted on people’s attitudes towards gay men?

Chris – [And] gay men’s attitudes towards themselves, yeah, definitely, and quite negatively, you know. [There was] the condom issue and the campaign with the tombstones and everything else and a leaflet going through every door in Britain, you couldn’t escape it, you really couldn’t escape it, and very quickly from ’80, ’81 people were actually being diagnosed and the first gay man who was diagnosed that I knew, was a friend, and of course then you think, ‘Oh my God!’. He was ill when he was diagnosed so he already had liver complications with diagnosis and deteriorated within a year and a half, two years, and died. His then long-term partner was positive and other really close friends that had been in that circle and had been intimate, one by one were being diagnosed positive.

Chris saw the impact that the disease was having on individuals he cared about but also the impact that it was having on attitudes to homosexuality. Yet, despite increased opprobrium directed at gay men, responses from LGBT organisations were not tempered by hostile attitudes:

JM – How did that impact on a political level in your life?

Chris – Yeah, I think that was just another injustice really. It all goes back to London, the sort of Stonewall era and Terrence Higgins Trust and a lot of the things that came up then I don’t think would have surfaced in such a strong, such a political way had it not been for HIV. HIV and the reaction or the backlash against, particularly, gay men at the time meant [that in a way] those organisations gained incredibly in power and status. [That happened in] Scotland as well because Scottish Aids Monitor were seen as coming and doing something for a community and were put there and funded because they were there to prevent or limit this outbreak within a community but I don’t think even at that stage there was the acknowledgment that the gay scene is not the only the ‘scene’… there’s a far larger percentage of men who have sex with men who don’t and will not put that tag on themselves or be put in that box.

For Ed, who spent time in Australia as well as Scotland, the emergence of HIV/AIDS had a cataclysmic impact upon his life and the lives of his partner, friends and family. Ed was not out to his closest family members and an HIV+ diagnosis prompted him to attempt to tackle issues relating to his sexuality and his health:

Well, it was a double whammy actually: my partner had died of AIDS and I got tested and [the test result] came back positive and I thought, ‘Right! I’ve got to tell them all’, so with my mother it was a double whammy, with her letter I wrote, ‘Dear Mum blah, blah, blah, not only am I gay but I’m HIV positive’ and she wrote back saying that ‘the main thing is that you keep healthy but I think it’s against nature that you’re gay’, just a short reply…

Ed has now been living with HIV for over 20 years, something that was unthinkable at the time:

Well, I was thinking about that a few weeks ago and thinking that it now all seems like a dream…you were going to so many funerals from that period, the late 80s right through to 2000, 2001, so many friends that had died. Well, you knew it was there and you were going from week to week to see who the next one was going to be and so you just had to get on with your life and basically, em, accept and deal with what was happening….and I look at it this way: you either accept what is happening or you just turn your back on it and go off and end it all…

Duncan recalled how the appearance of HIV/AIDS in Scotland impacted upon the attitudes and behaviour of many gay men:

I went doon to see a pal in London recently who had moved down from Glasgow and….he says, “Duncan, do you remember the days in Glasgow when it was just like a chocolate box and you could pick and choose any flavour or any variety you wanted, hard, soft?” and it was true, it was a very carefree…no awareness of AIDS and HIV and anything like that, you know, in these days and everybody was…I cannae say promiscuous, because that isn’t the right word for it, but there was a lot of people who were very active…But then, quite quickly, all of my friends were talkin’ about they’ve maybe knew somebody who actually had contracted HIV an’ once ye knew maybe one person or maybe two it really shoots it home to you and you just started to change your behavior.

Other gay men were overwhelmed by the power of AIDS, not just relating to illness, but the way in which terms such as HIV and AIDS had the potential to obscure the individual, their personalities, who they were:

Greg – I had a friend, who was quite ill herself, who volunteered at a hospice, and one afternoon she brought two guys with AIDS to a café near where I worked. I had met them both before, and my friend invited me to join them for a coffee. I’m ashamed to admit that I didn’t really want to face them. I went and I felt so powerless, so impotent. One of the guys was really very poorly and had mild dementia, and being frank, I couldn’t handle it. I’m ashamed of that, as gay man, I am ashamed of that.

HIV and AIDS also had an impact upon the LGBT rights movement in Scotland during the 1980s and 1990s. As mentioned, decriminalization had only occurred in 1980 and just as LGBT organisations were beginning to find their feet, and their voices, the hysteria amongst sections of British society and the British press had implications for non-heterosexual Scots.

Ed – Oh the nonsense, the sensationalism, the terrible way they treated children who were positive and they weren’t allowed to go to schools, and people were terrified to touch, you know. How they treated [them] in hospital at the beginning was terrible, sliding paper trays through the door to the patients, that sort of stuff, thank God that’s all gone.

Ken too lamented the emergence of further stigmatising discourses concerning the ‘gay plague’ just as confidence amongst sexual minorities was growing.

I think that was a sad thing and a difficult thing…there was parity in 1980 but things don’t change overnight, Joe Public was [still largely homophobic]…so maybe by ’82 we were starting to get somewhere but then [there was] the ‘gay plague’ in America, by ’86 it was here, so there was only that little window [of hope].

These recollections of the 1980s and 1990s are not peculiar to Scotland, but it is notable that the threat of HIV and AIDS emerged in Scotland so soon over after decriminalisation. This had implications for the development of LGBT movements, but despite considerable hostility and homophobia the pressing need for directed health services, and advocacy groups meant that voices silent for so long still demanded to be heard.

Copyright © Jeff Meek 2014

All Rights Reserved.

Please do not reproduce content from this blog in print or any other media without the express permission of the author.

Feelings of Nostalgia and Disconnection among Gay and Bisexual Male Elders in Scotland

Andrew King’s recent piece about older people and homophobia published on the website The Conversation got me thinking about my own research interviewees with gay and bisexual male (GBM) elders, which I undertook in the mid 2000s.

One of the notable issues concerning the homosexual law reform movement in Scotland during the late 1960s and 1970s was that it took on a largely ‘assimilst’ rhetoric. The Scottish Minorities Group (SMG), Scotland’s foremost homosexual law reform organisation believed firmly in the integration of LGB Scots into mainstream society, and demonstrated a sceptical attitude towards more radical organisations such as the Gay Liberation Front. Whether his was the result of a keen understanding of the cultural temperature of Scotland or a deeply held belief that assimilation was most desirable is debatable. What is not open to debate is that the SMG were successful in their campaign. However, some members were uncomfortable with this desire to conform; during the 1970s SMG were to suggest that although the use of police agents provocateurs to catch queer men cottaging was quite wrong, yet they also suggested that men who cruised for sex suffered from behavioural or mental difficulties.

When I interviewed two dozen older gay or bisexual men I was keen to understand whether assimilation and conformity was something that they had sought. Or had they been influenced by more radical approaches. ‘Brian’, born in 1936, saw more radical, politicised campaigning as unnecessarily confrontational. He included PRIDE events in this:

I’ve never taken part in [PRIDE]…and I don’t think I ever would; not my scene… Self-advertisement, there is a lot of that in it too, you know… But there is a certain breed of homosexual that wants to challenge all the time, they want to thrust it in your face.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Brian never participated in the gay rights or homosexual law reform movement, but does donate to LGBT support groups and charities. Brian was content separating his life into public and private spheres, only occasionally merging the two. Brian also feels uncomfortable about the contemporary gay ‘scene’; never venturing into gay bars. For Brian the ‘queer scene’ during the 1950s was governed by discretion, a quality that he has become rather nostalgic about. A lack of discretion, according to Brian can be problematic for today’s generation of LGBT Scots, as he described in a recollection of the experiences of a younger gay neighbour:

Until quite recently there were two gay boys living in this street. Funnily enough they had told me that certain people in this street actually shunned them because they were a gay couple. Now, I can believe it up to a point but I think that one of them in particular was kind of challenging people all the time to acknowledge him. He would go on about how they refused to acknowledge my partner…there was this sort of aggressive thing about, ‘You’ve got to recognise me for what I am and not for something else’. Is that necessary?

Nostalgia for a previous, less ‘complicated’ era may sound rather contradictory. The era is which my interviewees operated was an era where homosexual acts were illegal (although rarely prosecuted unless they took place in public), so discretion was not a choice it was a necessity. All of my interviewees were pleased that things have changed in Scotland, and many were envious of today’s generation who largely avoid engrained homophobia and scepticism. Yet, for some, something had been lost.

Robert, born in 1937:

It’s that slight double life thing and there is a feeling of pleasure in that. [It] fed something in me.

Yet, despite the ‘simplicity’ of the double life, it has left its mark on Robert’s ability to engage with a modern generation of GBM, and engage in meaningful relationships:

I’m deeply fucking annoyed that I have got to this age and I’m still so unfulfilled in areas of having a good connecting relationship and what fucking chance do I have now because of age and there is a bit of me that knows that I can’t do it but I do feel quite resentful that I have been deprived of that…

Alastair (b. 1948) was also quite nostalgic about being queer in Scotland during the 1960s and 1970s:

[There was a] lot of excitement because there was so much going on and whether or not it was legal didn’t actually matter too much. I can’t remember anybody having a great celebration party when the law changed, it just happened. [There was] a little bit of fear and a GREAT deal of excitement. The 60s were so exciting anyway and you know what they say, if you remember the 60s you weren’t there but I do actually remember quite a lot about it and the 70s were pretty wonderful too!

However, one must be careful not to assume that because Alastair, Robert and Brian enjoyed the excitement and thrills of queer life in post-war Scotland, that they were unconcerned about the denial of basic human rights to non-heterosexual men. Perhaps there is a temptation to view the years before decriminalisation as characterised by unrelenting misery, loneliness and isolation but what became clear from my interviews was that queer men created opportunities for pleasure, sex, love and companionship.

When I asked Morris (b. 1933) if he was in any way envious of young LGBT Scots of today he gave it considerable thought:

[Long pause] I think they are enjoying a remarkable freedom….I think they are lucky and yet at the same time, I don’t know. [It’s much easier now] and maybe they just don’t appreciate that. It was fun when you are being criminal you know, and getting away with it, it was fun doing it right under their very noses. You were having the time of your life and they didn’t know, well you hope they didn’t know!

Morris told me he would much rather have experienced queer life today as a young man rather than queer life in the 1950s but, at the same time, he would not change his past. His experiences, good and bad, helped form who he has become. However, the dramatic shift in lived experience for GBM today as compared to 50 years ago has led, in many instances, to a feeling of disconnect for some of my interviewees. I’ve already detailed Brian’s frustration caused by, in some part, so many years living a double life. Other interviewees told me how they find it difficult or challenging to relate to the ‘younger generation’.

Chris (b. 1958) told me:

When I am talking to gay men just now who are their teens or 20s it’s something they don’t even think about it [the struggle]… Just to be on that Gay Pride march every year in the early stages when people would throw things at you, was a political statement…

For Chris and other interviewees, the past was not another country: it played a part in forming the fabric of today, and some queer Scots of a younger generation are unaware or perhaps unappreciative at the endeavours, both personal and political, of their LGBT elders. While Joseph (b. 1959) has great admiration for this younger generation of LGBT Scots, who he believes, in the main, are aware of past sacrifices and battles, he does believe that commercial interests now dominate the ‘gay community’, which has been reshaped to attract certain groups:

I’m trying no’ tae generalise as it’s important no’ tae generalise but I do find on the commercial gay scene that there is an ageism which is very prevalent. I don’t actually buy into the idea that the gay scene is necessarily welcoming and affirming to everybody. I think individuals in that scene are but I don’t think that the commercial gay scene as a whole necessarily is and I think there is a lot of discrimination at work. You go to [a popular Glasgow gay bar] and you hear young people say, “What’s that old bastard doing here?”

Of course, ageism isn’t restricted to aspects of LGBT communities but is perhaps more pronounced due to its spatial limitations. Colin (b. 1945) acknowledges the problems of elder LGBT visibility, not only within queer commercial enterprises but within wider society, ‘it’s as if they’re not there…invisible’, but accepts that when he was younger and visiting gay bars in London he also participated, to some extent, in this process: ‘I was drawn into that consumerist world’. Joseph argued that LGBT life should not be measured by the merits and failures of a commercial LGBT ‘scene’, which he feels has been dressed up as being reflective of LGBT experiences. He argued that for many years the LGBT commercial scene was more a ghetto than a community; a place where a marginalised group could theoretically meet, communicate and engage. But as with most ghettos, Joseph feels that it offers you what you want/need for a while until A – you need or are able to find something more rewarding, or B – you no longer feel part of it, or are excluded.

My interviews with these GBM over 50 offered an alternative view of ageing, connection and disconnection, community, and isolation experienced by a sexual minority in Scotland. None of these men wished a return to some sepia-tinted, halcyon queer past but wished to make two main points: queer life during the post-war period wasn’t all misery, gloom and furtive fumblings; there was colour, vigour and plenty of evidence of how queer men shaped their own experiences in the face of hostility, homophobia and potential criminalisation. Secondly, the march of progress, and widening rights was met with relief and joy by these men but they were conscious of how their experiences had led to a measure of disconnection with a later generation of LGBT Scots.

Buggery, Body Snatchers and Bewitchings

Throughout early modern and modern history homosexual acts have been the focus of condemnation, religious outrage, penal sanctions and considerable suspicion. In the 16th century further connections between the act and sinister superstition were made, contradicting earlier works which suggested that even demons drew the line at buggery. The new narrative claimed that witches, in particular male witches, engaged in diabolical sex (I’m sure we’ve all experienced this) and is evident in the, admittedly rare, references to sodomy in 16th and 17th century Scotland. Michael Erskine was accused of engaging in both sorcery and sodomy in 1630 and on being found guilty on both charges was burnt at the stake. Half a century earlier, a John Litster and John Swan shared a similar grisly fate.

While the Dutch were busily garroting ‘sodomites’ during the 18th century, the Scots, particularly legal theorists, were ambivalent on the thorny issue of same-sex desire. Whilst some classed it amongst the ‘sodomitic sins’ (including buggery, bestiality, and opposite sex ‘unnatural fornication’), others such as John Millar viewed sodomy as a victimless crime (although it still warranted punishment). However, the taint of the diabolical apparently remained reasonably strong in popular discourses of same-sex desire well beyond the age of enlightenment. Take for example the case of George Provand, a successful young Glasgow oil and colour merchant, whose home in West Clyde Street was attacked and vandalised in early 1822. Provand’s tale of terror has been told numerous times on Glasgow local history sites and by the well-known Glasgow journalist Jack House in his book The Heart of Glasgow. According to these popular sources, Provand was accused of abducting local children, butchering them and adding their remains to his oils and colours. One ‘witness’ swore that he saw in Provand’s basement a flowing river of blood upon which bobbed the decapitated heads of children. Provand was also accused by the mob of being involved in black magic, or, in the supply of fresh corpses (albeit missing their heads it seems) to medical instructors. There seemed no end to Provand’s devilish pursuits.

However, what these popular sources often ignore is that he was also accused of inviting the sexual favours of young local men. The riot, which led to the ransacking of Provand’s mansion, may have been instigated by the claims of 17 year-old John Graham (amongst others) who stated that Provand had paid him 6d ‘to work his privates’ (a description which occurs frequently in cases relating to homosexual acts). Criminal charges were laid against the rioters and looters, with one ‘whipped through the town’, and another 4 sentenced to transportation. Provand was charged in April of that year with sodomy and was initially found guilty. His failure to appear in court led him to be outlawed and ‘put to the horn’, but ultimately the allegations were viewed as being an attempt to discredit the victim of (or to justify) violent crimes. Whether Provand did enjoy the regular physical company of men is open to debate but these accusations grew legs and ultimately alluded to demonic pursuits, which although hysterical, bring to mind the accusations made against 16th and 17th century male ‘witches’, whose fates were considerably bleaker than Provand’s.

Further Reading

Theo van der Meer, ‘Sodomy and the Pursuit of a Third Sex in the Early Modern Period’ in Third Sex, Third Gender: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism in Culture and History, ed. by Gilbert Herdt (New York : Zone Books ; Cambridge, Mass. : MIT Press, 1996, c1993), pp. 407-429

Tamar Herzig, The Demons’ Reaction to Sodomy: Witchcraft and Homosexuality in Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola’s “Strix”, The Sixteenth Century Journal , Vol. 34, No. 1 (Spring, 2003) , pp. 53-72

James Adair: Lord Protector of Scottish Morality

Few names will stir the emotions amongst LGBT Scots, who were alive during the deliberations of the Wolfenden Committee, than James Adair OBE. Adair wasn’t the only Scot to sit alongside John Wolfenden, but he is probably the most in/famous. He was to disagree fundamentally with the recommendations of the committee regarding homosexual offences and produced a minority report that questioned the moral reasoning of decriminalising homosexual acts between men.

In the 2007 BBC 4 drama, Consenting Adults, Adair was played as a somewhat disagreeable and pompous man, by the actor Sean Scanlan. Just how pompous and disagreeable he was is difficult to ascertain as we know so very little about this former procurator-fiscal, who had a long and successful career as a prosecutor. What we do know is that he was an elder of the Church of Scotland who grabbed many column inches through his unwavering opposition to homosexual law reform. He lived to see the change in law in England and Wales in 1967, and in Scotland in 1980, as he died in January 1982 at the ripe old age of 95 (this is despite being ‘killed off’ by Lord Ferrier – Victor Noel Paton – in a debate regarding homosexual law reform in Scotland, in 1977). Adair outlived his wife Isabel, by 32 years.

The purpose of this blog post is to flesh out the rather one dimensional view we have of Adair, whose portrait above does little to add personality or vigour to the name. Born in Barrhead in 1886, Adair was the eldest son of William, an iron turner and Catherine, and he grew up in George Street and Barnes Street, Barrhead. On leaving school at 13, young Adair took employment as a clerk in a local legal office. Adair was obviously motivated by this early exposure to the legal profession, as he studied law at Glasgow University, eventually qualifying as a solicitor in 1909, and entering private practice in criminal defence, serving his apprenticeship with Glasgow solicitors Brownlie, Watson & Beckett. In 1919, at the instruction of J. D. Strathern, he was appointed procurator-fiscal depute, with his first case, the George Square Riots of 1919. In 1933, a year after he transferred to Edinburgh, he was involved in the Kosmo Club trial regarding ‘immoral earnings’. In 1937, he succeeded Strathern as procurator-fiscal at Glasgow.

Adair had a particular interest in morality, perhaps fostered by his membership of the Church of Scotland, and was associated with the National Vigilance Association of Scotland, particularly during the period of WWII, when he was delighted to announce to the NVAS that in Scotland the war had resulted in very few ‘fallen women’. Away from his legal and moral duties, Adair was to build a reputation as an entertaining public speaker on topics such as; Old Glasgow Streets, Old Glasgow Characters, and Edinburgh Life. He also had a long association with the Scottish Burns Federation (I wonder what he made of Burns’ ‘interesting’ sexual life), and with the Young Men’s Christian Association (he was the chairman of the Scottish National Council & from 1962, World President).

But it was Wolfenden that pushed Adair onto the public stage. Adair’s greatest fear was that law reform would have a devastating effect on the young in Scotland (Lord Arran appears to have picked up this particular baton recently). He stated that: “The presence in a district of…adult male lovers living openly and notoriously…is bound to have a pernicious effect on the young people of that community”. Adair’s proclamations of doom were seized upon by the Scottish press, with The Bulletin & Scots Pictorial lauding his input: “We should be glad if the things discussed…could be wiped out altogether…There is not much doubt that this disgusting vice has been becoming…more ‘fashionable’…”. The Scotsman took a similar editorial stance, and the Daily Record could barely conceal its outrage. Speaking at the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1958, Adair caused panic in the cloisters by claiming that within weeks of the publication of the Wolfenden Report, a homosexual ‘club’ in London, offering information on meeting places including public lavatories, had received nearly 50 applications for membership, and in one square mile of London there were over 100 male prostitutes offering depraved services. Adair’s fear was that any change in law would enable ‘perverts to practice sin for the sake of sinning’ in Scotland.

Yet, there was an element of mendacity about Adair’s claims. He would have known, first hand, that homosexual prostitution was already thriving in Scotland by the turn of the 20th century and by the 1920s there were organised groups of male prostitutes operating in Glasgow – a city, he had previously hinted, with a a greater attraction for gay men. In reality Adair was upset that the previous policy of ‘silence’ regarding same-sex desire in Scotland was under threat, and by emphasising the potential for moral turpitude, he hoped to consign homosexual law reform in Scotland to the dustbin. In any event this was what effectively happened due to the peculiarities of Scots Law. Adair became a representative, a figurehead, for moral objections to homosexual law reform in Scotland, and would have been quietly satisfied that within a few months of the publication of the Wolfenden Report, Scottish silence had been restored (albeit to be resurrected in the mid 1960s, but with a similar result). Adair, his job done, could retire into relative obscurity, appearing now and again from his home in Pollokshields to offer a talk on old Glasgow, or to attend meetings of The Galloway Association of Glasgow.

Copyright © Jeff Meek 2013

All Rights Reserved.

Queer Places

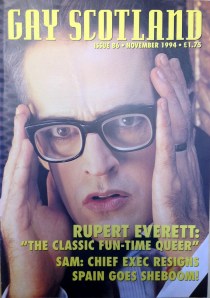

Recently I inherited (after a colleague retired) a large collection of LGBT magazines and ephemera stretching back to the early 1980s. These include numerous editions of Gay Scotland and Gay Times, which are helpful resources when examining the development of LGBT culture over the past 30 years.

Take, for example, this issue of Gay Scotland from Jan/Feb 1984 – a Science Fiction special. At this time the magazine had a circulation of around 8,000 with the majority of readers subscribing or buying a copy from gay bars and clubs. What is noticeable from the content is that the magazine contains significantly less advertising space than more recent magazines, and offers a plentiful supply of news items, which are unsurprisingly related to LGBT interests and the continuing pursuit of equality and an end to discrimination.

What interested me was the section ‘Scenearound’ detailing places and spaces for LGBT Scots to socialise. A snapshot of the gay ‘scene’ in 1984 offers some opportunity to consider how the ‘scene’ had developed after 1980. There were gay/mixed spaces prior to 1980; in Glasgow; there was the Close Theatre bar, Guys, The Royal, the coffee bar in the Central Hotel, Top Spot Mexicana, The Strand, the Corn Exchange, and Tennent’s to name a few, but after 1980 there was growing confidence that commercial premises catering for the LGBT population could be profitable and offer a safe(r) experience for Glaswegian LGBTs.

According to the listings there were 13 gay or gay ‘friendly’ pubs ‘n clubs in Glasgow in 1984. Some will be familiar to those of us ‘of a certain age’: Court Bar, Squires, Tennents, The Waterloo, Bennets. But there are more: Bardot’s at 72-74 Broomielaw, incorporating La Maison & Le Village; Studio One on Byres Road (mainly Sundays); Vintners, Panama Jax, and Halibees Cafe Cabaret. However, due to the transient nature of many ‘gay’ venues, by November Bardot’s seems to have disappeared, and Halibees is no longer listed. New entries include Cul de Sac on Ashton Lane, Chippendales on Clyde Street, & The Winter Green Cafe. Editorial notes offer readers a glimpse of what to expect: Duke of Wellington – ‘rough, but ready clientele’; Vintners – ‘busy [and] cruisy’; Cul de Sac – ‘trendy…popular with a certain ‘set’; Squires – ‘up market…popular with tourists’.

If we leap forward another 10 years to July 1994, Glasgow had 16 venues listed, including a new generation of gay pubs ‘n clubs; much more commercial and appealing to the ‘pink pound’ younger market. Café Delmonicas, Club X, and Mondays at The Tunnel boasted a much more music-oriented culture. The ‘old guard’ were still represented by the Court Bar, Squires, The Waterloo, Austins and, to some extent, Bennet’s but the 90s saw the emergence of a distinctly different form of gay leisure culture. This new culture was characterised by a more confident and market-savvy approach that relied upon a younger and more affluent customer base. Characterful, they were not. But this gay scene was replicating the changes that were occurring more broadly within the leisure industry, which was becoming a more customer-driven platform, and introduced a new phase in the evolution of gay commercial culture in Scotland which saw an alignment with the mainstream.

The language of gay Scottish leisure changed too. Whereas venues in the 1980s might have been described as ‘discreet’, ‘cruisy’, ‘closeted’ or ‘tolerant’, by the mid 1990s such descriptions were absent. These changes were replicated in the LGBT publications of the period too, which reflected increased revenue, appeal, and confidence and were able to expand content to include more than activism and awareness of LGBT issues.

A similar progression can be seen in Gay Times between 1984 and 1994:

The ‘streamlining’ of commercial gay culture in Scotland has led, in some instances, to the narrowing of its appeal. Modern venuesmay be guilty of permitting market forces to disregard sections of the community: the older and less well off, in its drive for profitability and commercial appeal, with LGBT 0ver 50s frequenting venues in fewer numbers. This was certainly a feature evident from my research with gay and bisexual men over 50; some of whom felt that this drive towards profitability over community was gradually excluding the more mature or alternative ‘markets.

Copyright © Jeff Meek 2013-2023

All Rights Reserved.