Scotland’s Queer Heritage

Exploring environments across Scotland, 14 writers share the places and spaces which define their queer history.

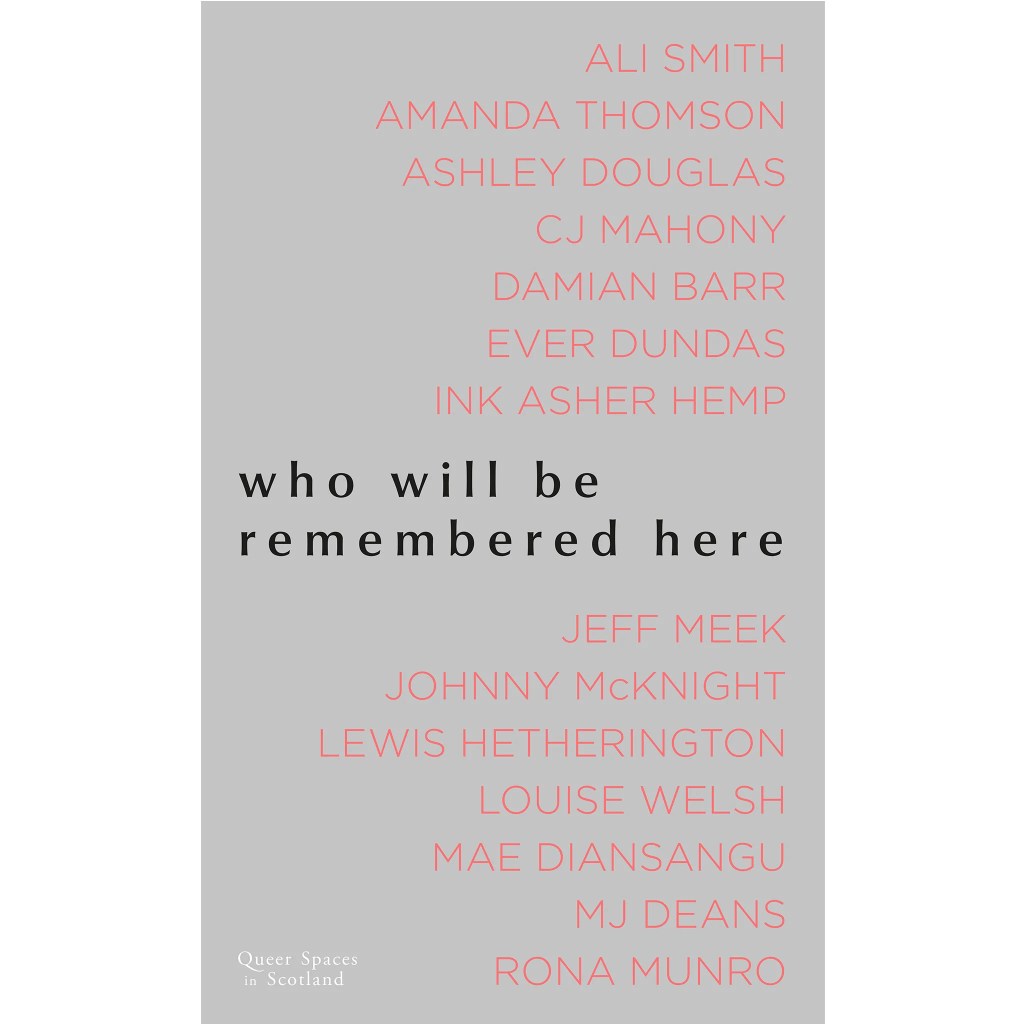

who will be remembered here reconsiders and reimagines the built and natural environment through a queer lens, uncovering stories full of hope and humanity, and the collection features images from HES archive.

Contributors are Ali Smith, Damian Barr, Ink Asher Hemp, Mae Diansangu, Ashley Douglas, Amanda Thomson, Jeff Meek, Rona Munro, MJ Deans, Louise Welsh, Ever Dundas and Johnny McKnight, along with Lewis Hetherington and CJ Mahony who are also the book’s curators. The book features works in English, Scots and Gaelic.

2025 marks a significant point in LGBTQ history, being 30 years since the first major Pride event in Scotland. Queer history is an important part of Scotland’s past, but it is largely absent from records. By making invisible stories visible, who will be remembered here ‘captures something of the richness, complexity and beauty of a history that belongs to all of us’.

The book will be released in the 14 of August and can be pre-ordered.

Calling All Budding Writers

How do fancy writing for Queer Scotland? Sadly there is no budget, so we rely on the generosity of strangers. Indeed, recently we had a whip-round for tea-bags. But, if you fancy yourself as budding writer/journalist/busy-body, then this would a step in that direction. If you have ideas for LGBTQ historical content, please get in touch: jeff@queerscotland.com.

Oban Lesbian+ Weekend 2025, 5-8 September

SCOTLAND’S LEADING 3 NIGHT LGBTQ+ WOMEN’S WEEKEND

WE’RE BACK FOR A 4TH YEAR!

Oban Lesbian Weekend is an inclusive weekend, run by LGBTQ women and non-binary people for LGBTQ+ women and non-binary people. It is not for us to police what % lesbian our attendees are! All are welcome – the rules are simply treat others with respect!

If you have any questions! Email us at: obanlesbianweekend@gmail.com

An Extraordinary Career: Marie alias Johnnie Campbell, 1871

RENFREW, November 1871

A fog had descended over Renfrew, swept in by the brisk November winds. Dr Allison turned his collars up against the chill and peered through the gloom, spying the address on Pinkerton Lane where a desperately ill young man awaited his attention. Discarding his cheroot, the doctor knocked firmly on the front door. He heard steps approaching and the door opened to reveal a tidy, middle-aged woman.

‘Mrs Early?’, Allison enquired.

“Aye doctor. Come in, he’s no’ well at aw!”

The doctor was led through the house to a dimly lit back bedroom, where a figure lay still, illuminated by a single candle, the dancing flame reflecting off his sickly pallor.

Dr Allison approached the patient. “Mr Campbell?” The man nodded, weakly wiping sweat from his brow.

“My back aches”, moaned Campbell, “and my head is fit to burst!”

Dr Allison noted the young man’s light voice, a weakness perhaps? Yet, as the doctor’s hand brushed the man’s cheek, he could not help but notice the smoothness of the skin. The doctor lit another candle and his patient recoiled, pulling the bedclothes further towards his chin. His hands gripped the woollen blanket; they were small hands, chubby with short fingers. He examined the patient, taking his temperature and checking his glands. He tutted loudly.

“Mr Campbell, I am in no doubt that you will need to accompany me to the Infirmary,” said the doctor, placing a reassuring hand on Campbell’s shoulder. “This is a most grave fever.”

The young man closed his eyes and muttered, “That, I cannot.”

“Then I’m afraid,” began the doctor, “you may breathe your last in this room. Your salvation is the hospital. There we can administer treatment that may very well prolong your life.” Campbell was still resistant.

“No,” he responded weakly, his eyes barely opening, “hospital presents all manner of risks.”

The doctor brought his face to within inches of his patient’s.

“Is it because of your sex?”

A New Life in Renfrew

When John Campbell had fallen ill with smallpox, he was residing as a lodger with the Early family in Renfrew, while he laboured at the local shipbuilders, Henderson, Coulborn and Co. Thomas Early had known ‘Johnnie’ for some time, striking up a friendship while they had worked farms in West Lothian, before Early and his wife settled in Renfrew. John had returned to East Calder where he courted and then married Mary Ann McKenna and had begun married life in Kirknewton. Their marriage had raised some eyebrows locally as McKenna’s reputation had been sullied by the birth of two illegitmate children, Julia and Francis, before she was twenty years old. However, the marriage was seemingly illsuited to both parties, and John had left the marital home within 5 months.

When Johnnie had arrived in Renfrew in search of work, he had contacted his friend Thomas Early, who had been happy to offer room and board. Mrs Early later reflected on just how amiable, agreeable and helpful Johnnie had been since his arrival, often helping her in the kitchen, and fellow lodgers with darning and sewing. So attentive had Johnnie been when Mrs Early fell ill with influenza that her husband had become quite jealous of their intimacy. Yet, Johnnie was much more interested in local lass Kate Martin whom he treated to trips to Edinburgh and with whom he shared many of his evenings. Johnnie, throughout his time since leaving Kirknewton, ‘adhered to the old habit of loving and associating with the lassies’. But what Kate and the Earlys were unaware of was that Johnnie had deserted a wife and three children in Kirknewton to start his life afresh on the west coast – the marriage had seemingly produced a third, legitimate, child.

In Kirknewton, Johnnie’s deserted wife Mary Ann had been brought before parish authorities who demanded to know where her husband was, and why he was no longer financially supporting his family. Mary Ann, fearful that her relief would be stopped made a quite extraordinary claim.

“John Campbell is not my husband.”

That was impossible stated her interrogators, for they possessed a copy of the marriage lines.

“I’m am not denying that we stood before God and made our commitment. But it was a fraud! For John is not John, she is Marie.”

A Life Unravels

The parish board dismissed Mary Ann’s claim. Surely a minister with the experience of Henry Smith would not be fooled by such an alleged masquerade? It was simply outrageous. She had also admitted that her recently born child was not her husband’s. So, what was it to be? Was her husband a woman, or, had Mary Ann deceived him and bore another man’s child? Perhaps, filled with betrayal and torment he deserted her? The latter explanation was much more palatable to the authorities; Mary Ann had already bore two illegitimate children. Her habit of lying with men that were not her husband had blackened her reputation. The board were resolute. Mary Ann was a liar and a reputed harlot. They had already experienced Mary Ann’s mendaciousness when investigating the paternity of her two previous illegitimate children, two children whom John Campbell had happily agreed to bring up as his own.

One can only imagine the consternation when news reached Kirknewton of an extraordinary case of fraud from Renfrew involving a woman posing as a man named John or Johnnie Campbell. The parish board gathered together a delegation to travel to Paisley Infirmary to investigate this ‘fraud’.

Mary Ann accompanied the Kirknewton Inspector of the Poor, and Will Waddell who had been a witness at the wedding, to Paisley Infirmary. On seeing her husband in a hospital bed in a female ward, Mary Ann exclaimed, “There she is, my supposed husband!”. John, or Marie, who was now attired in a nightdress, exclaimed, “Is that you Will Waddell? How’s the wife an’ bairns?”

When questioned, Marie claimed that Mary Ann had known full well about her sex: “Mary Ann knew that I was a woman; it was to make us more comfortable that we lived together”. Mary Ann however, claimed that she had married John, then a shale pit labourer, in good faith, and that the revelation had only occurred after the wedding. It seems that unlikely that revelation took so long to occur, as the couple had cohabited for 5 months before John’s desertion. Whatever the truth, Marie Campbell, alias John or Johnnie Campbell, had embarked on an extraordinary career from an early age. Her older brother, on his deathbed, had advised his sister to make her way in life as a man, for a woman’s lot was not a happy one. An alternative reason was given by Marie that she had been subject to ‘bad usage’ at a young age and for her own state of mind and security attired and lived as a man. From the age of 15, John of Johnnie, had worked in various labouring roles, from road surfacing to mining. In the language of the day many people, like Johnnie, may have struggled to accurately and publicly describe their own feelings. They also had to consider the potential opprobrium directed their way by a society largely ignorant of diversity.

Despite the shock that the revelations brought to those who knew Johnnie Campbell, few had scornful words. Former colleagues in Renfrew started a subscription to support their former colleague, stating that “a more kindly and obliging worker never was engaged in the yard”. The Earlys, particularly Mrs Early, thought of Johnnie with such fondness that she could not condemn. Marie faced charges under the Registration Act for fraudulently contracting a marriage; Mary Ann returned to West Lothian; and life in Pinkerton Lane returned to normal. Yet, everyone who knew Marie, alias Johnnie Campbell continued to remember fondly, the young person who had touched their lives.

History does not offer us an opportunity to ask questions of the long deceased, to explore their motivations, and it is difficult to apply 21st century definitions or labels. But it does enable us to demonstrate that within Victorian Scotland, attitudes towards ‘non-conformity’ were not necessarily all negative. Johnnie/Marie was liked, loved even, by the individuals they met and worked with. Prosecution did follow, but for misusing the legal institution of marriage and for fraudulently registering a marriage, and not for any issues relating to sex, sexuality or gender.

Langside Hall: A Concise History

By the midpoint of the 19th century successful businesses wished to build offices that reflected their optimism, growing wealth and confidence, especially at a time when Glasgow was cementing its position as the second city of the Empire. One such organisation, which emerged during the early part of the century was The National Bank of Scotland (NBS) (established in 1825) and after a failure to acquire the Glasgow and Ship Bank, the NBS undertook to open their first Glasgow branch in 1843. Occupying temporary accommodation in the first instance the bank launched a public competition to design a more suitable building. A young London architect, John Gibson (1817-92), then working under Charles Barry, entered the competition and his plan was unanimously chosen as the winner. On Gibson’s first official trip to the city he was treated to a public dinner given by the ‘principal gentlemen of Glasgow’ and commented that ‘I was much gratified by the kindness shown to me in Glasgow, and surprised to see so many public monuments, and all by the best sculptors’. After the final plans were approved construction of the new building, in Queen Street, began that winter and was completed within 4 years.

According to ‘The Glasgow Tourist and Itinerary’ (1850) the completed building was ‘commodious and elegant; the telling-room being elaborately ornamented, and its polychromatic decorations [executed by H. Bogle & Co., Glasgow, house painters to the Queen] are tasteful and appropriate’. An article in The Civil Engineer and Architect’s Journal in September 1849 confidently stated that ‘there is not yet one building of the class in all the metropolis which offers anything like the same degree and completeness of embellishment’.

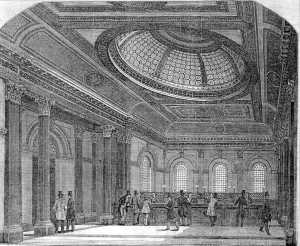

An engraving of the National Bank building, 1849

The exterior of the building was similarly lauded for its beauty. The building’s inspiration was to be found in the work of Vincenzo Scamozzi, the Venetian architect, with the ground floor rusticated with five arched openings, the centre opening housing the doorway. The entrance is flanked by double Ionic columns. The windows are separated by pilasters (flat columns, flush to wall), which appear in double form at the corners of the building. The original door was of a bronze-green colour and was ornamented with bronze paterae (circular ornaments) and studs.

The Telling Room of the Bank

The architectural design of the building was impressive but was further improved by the addition of sculptures designed by London’s John Thomas (1818-62), who was to work often within Glasgow, and worked on the Houses of Parliament, Balmoral, Windsor, and Buckingham Palace, and became a favourite artist of Prince Albert. The Prince commissioned Thomas to create two large bas-reliefs of ‘Peace’ and ‘War’ for the latter palace. Thomas was to create the Graeco-Egyptian Houldsworth Mausoleum at the Necropolis and the designs for the industrialist Houldsworth’s new home at 1 Park Terrace. For the National Bank, Thomas ornamented the windows with carved keystones representing major rivers of Britain (the Clyde, Thames, Tweed, Severn & Humber – although there has been some dispute as to whether the latter two were in fact the Shannon and Wye).

A small bust of Queen Victoria was placed in the centre of the attic frieze. Portland stone Vase finials and the Royal Arms, supported by a unicorn and lion, ornament the roof frontage of the building which was faced with stone with a light-grey tint, supplied by the Binnie Quarries near Edinburgh, and the masonry was executed by John Buchanan. The side of the building was similar in design to the front but had only three windows per floor, divided by double pilasters. The rear of the bank had an out-standing gallery, within which stood another entrance which was ornamented by Ionic columns.

The interior of the building was resplendent with the telling-room of the bank boasting a 23-foot in diameter dome filled with colourful stained glass, provided by Ballantine & Allan of Edinburgh, who had also provided the stained glass for the House of Lords. The walls were decorated with columns and pilasters painted a deep red, with white bases and tops. Near the base of the pilasters a band of black marble framed the flooring. The frieze above the columns was adorned with roses, shamrocks and thistles. The ceiling, following this colourful design, was crimson, blue and gold, with this work being undertaken by the Glasgow firm, Bogle & Co. The floor between telling counters (carved from mahogany), directly beneath the dome, was paved with coloured marbles, which in the centre formed a radiating star. The telling-room was positioned to the rear of the building and the front area was to be found along a handsome corridor, adorned with panels of contrasting colours, which led to a committee room, manager’s room, and waiting room.

So enthralled with the design of the building, The Civil Engineer and Architect’s Journal (1849) enthused that ‘the Scotch seem to have got greatly ahead of us in tasteful as well as liberal decoration of places of public business’. However, such splendour, which had initially excited the Bank’s directors, was to lose its appeal as the 19th century progressed. By 1896 the NBS was seeking new and more suitable premises for its business in Buchanan Street, at the junction of Buchanan Street and St Vincent’s Street. In a letter to architects a representative of the Bank’s directors stated ‘My directors do not favour the idea of anything of the nature of elaborate decoration…and have expressed a leaning towards a thoroughly businesslike building…of chaste design’.

Thus, the future of the building appeared bleak by the tail end of the century. However, efforts were already underway to purchase the building from the NBS. In November 1896 an offer from Mr Richard H. Hunter, philanthropist and chairman of Hunter, Barr & Co Ltd, wholesale warehousemen & shipowners, was accepted on the provision that the Bank could continue to occupy the building for a further 4 years, while their new premises were constructed. However, this initial bid failed, but the same company made another offer in July 1898 to purchase the building for £59,000. The Bank rejected this bid and were holding out for an offer of £60,000, which they received in August the same year with provision to allow the bank to remain in the premises until 1901. Hunter was to retain the land from the sale and on this built the Hunter Barr Building (which still occupies the site today) designed by David Barclay.

From Bank to Public Hall: The Rebirth

One of the problems Glasgow Corporation had faced in supplying a public building for the Langside, Battlefield and Mount Florida districts (promised after annexation) was where to build. After annexation a committee was appointed by the ratepayers of the districts to negotiate with the corporation. After much discussion, bickering and frank exchange of opinions 3 main ‘preferred’ sites were identified: 1. The north side of Battle Place, on the Camphill Estate 2. The south side of Battle Place on ground owned by two proprietors 3. At the junction of Langside Avenue and Pollokshaws Road, also in the grounds of Camphill (the least preferred). Positioning the halls at the place of Queen Mary’s defeat at the Battle of Langside was initially viewed by the corporation as the victory of sentiment over practicality. In 1899 Bailie John Oatts suggested that the south side of Battle Place was the most preferred site but purchasing the ground would prove to be too expensive. The north side was problematic as the elevation of the ground would prove troublesome to builders. The land at the junction of Langside Avenue and Pollokshaws Road was problematic as the position of the new halls would favour the residents of one district. It would appear that the chosen site, the latter of the options, was a compromise.

Yet, the decision met with considerable protest from sections of the local community who took exception on two grounds: the encroachment onto the Camphill grounds & the geographical positioning of the new halls. Indeed, in 1901 a committee of ratepayers took their objections before Sheriff Guthrie and the corporation were accused of being ‘high handed’ while the objectors were accused of ‘humbugging’. Further, the objectors did not believe that the former National Bank building, newly acquired by the corporation, was fit for purpose. The building had not been retained by Hunter after he purchased the site in Queen Street and the offer of a ready-made public hall was too tempting for Glasgow Corporation to dismiss, even if it meant bringing it, brick-by-brick, to the Southside.

Once the lengthy discussions had ceased and legal objections had been rejected Alexander Beith McDonald was instructed to re-design the building’s interior (although the bulk of the work was undertaken by Robert Horn). A utilitarian building was needed so, regrettably, much of lavish interior was removed (the interior had previously been altered under the direction of James Salmon in the mid 1850s). The entrance was given a green-tiled hallway and a double staircase was constructed which led up to the lesser hall (with gallery), which when finished could house 320. The upper hall was designed to accommodate a further 100 souls, while the former telling-room was turned into the large hall, which could accommodate 850. Sadly, the splendid stained glass-filled dome was removed entirely and the plasterwork replaced. A reception room was designed to accommodate around 20 people, and several smaller spaces were created. The new Langside Public Halls were also equipped with cloakrooms, a buffet, and kitchen.

After much delay, deliberation and some dissent, the new halls for Langside were officially opened on the 24 December 1903. The Lord Provost John Ure Primrose, Baronet, was unable to attend due to a prior commitment and his place was taken by Councillor William Martin, the convener of the special committee of halls, Councillor W. F. Anderson and Bailie Finlay. Finlay, acting on behalf of the Watching and Lighting Committee accepted custody of the halls.

Councillor Anderson informed the gathered crowd that the builders who had re-erected the building using the 70,000 numbered stones recovered from the demolished bank building did so without seeking a farthing of profit, which was met with applause. Those attending the opening were treated to vocal and orchestral concert. This grand opening was covered by the Glasgow Herald and The Scotsman newspapers, amongst others, in their Christmas Day 1903 editions.

Over the past century Langside Public Halls have played a significant role in the south Glasgow community. The halls have figured prominently in the rich and diverse social and political history of the city, playing host to John Mclean and the famous Red Clydesiders (Maclean was arrested 4 times outside the halls), Sylvia Pankhurst and the Scottish branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union, and the Scottish Young Conservatives annual conference. It has been a true community hall where Glasgow Progressive Synagogue was temporarily based, where the annual Glasgow Congress ‘International’ chess event packed out the main halls, where the world famous Smetana Quartet of Prague performed in concert, and where the resident band The Crackerjacks filled the floor of the large hall in the 1950s.

John Maclean

The story of Langside Public Halls is a truly remarkable one. It is a story of architectural excellence and a story of survival. With the removal of the National Bank of Scotland, Queen Street Office to the southside of the city one of Glasgow’s most admired buildings survived to play a central role in the social and community history of the area.

Copyright © Jeff Meek 2013

All Rights Reserved.

James Adair: Lord Protector of Scottish Morality

Few names will stir the emotions amongst LGBT Scots, who were alive during the deliberations of the Wolfenden Committee, than James Adair OBE. Adair wasn’t the only Scot to sit alongside John Wolfenden, but he is probably the most in/famous. He was to disagree fundamentally with the recommendations of the committee regarding homosexual offences and produced a minority report that questioned the moral reasoning of decriminalising homosexual acts between men.

In the 2007 BBC 4 drama, Consenting Adults, Adair was played as a somewhat disagreeable and pompous man, by the actor Sean Scanlan. Just how pompous and disagreeable he was is difficult to ascertain as we know so very little about this former procurator-fiscal, who had a long and successful career as a prosecutor. What we do know is that he was an elder of the Church of Scotland who grabbed many column inches through his unwavering opposition to homosexual law reform. He lived to see the change in law in England and Wales in 1967, and in Scotland in 1980, as he died in January 1982 at the ripe old age of 95 (this is despite being ‘killed off’ by Lord Ferrier – Victor Noel Paton – in a debate regarding homosexual law reform in Scotland, in 1977). Adair outlived his wife Isabel, by 32 years.

The purpose of this blog post is to flesh out the rather one dimensional view we have of Adair, whose portrait above does little to add personality or vigour to the name. Born in Barrhead in 1886, Adair was the eldest son of William, an iron turner and Catherine, and he grew up in George Street and Barnes Street, Barrhead. On leaving school at 13, young Adair took employment as a clerk in a local legal office. Adair was obviously motivated by this early exposure to the legal profession, as he studied law at Glasgow University, eventually qualifying as a solicitor in 1909, and entering private practice in criminal defence, serving his apprenticeship with Glasgow solicitors Brownlie, Watson & Beckett. In 1919, at the instruction of J. D. Strathern, he was appointed procurator-fiscal depute, with his first case, the George Square Riots of 1919. In 1933, a year after he transferred to Edinburgh, he was involved in the Kosmo Club trial regarding ‘immoral earnings’. In 1937, he succeeded Strathern as procurator-fiscal at Glasgow.

Adair had a particular interest in morality, perhaps fostered by his membership of the Church of Scotland, and was associated with the National Vigilance Association of Scotland, particularly during the period of WWII, when he was delighted to announce to the NVAS that in Scotland the war had resulted in very few ‘fallen women’. Away from his legal and moral duties, Adair was to build a reputation as an entertaining public speaker on topics such as; Old Glasgow Streets, Old Glasgow Characters, and Edinburgh Life. He also had a long association with the Scottish Burns Federation (I wonder what he made of Burns’ ‘interesting’ sexual life), and with the Young Men’s Christian Association (he was the chairman of the Scottish National Council & from 1962, World President).

But it was Wolfenden that pushed Adair onto the public stage. Adair’s greatest fear was that law reform would have a devastating effect on the young in Scotland (Lord Arran appears to have picked up this particular baton recently). He stated that: “The presence in a district of…adult male lovers living openly and notoriously…is bound to have a pernicious effect on the young people of that community”. Adair’s proclamations of doom were seized upon by the Scottish press, with The Bulletin & Scots Pictorial lauding his input: “We should be glad if the things discussed…could be wiped out altogether…There is not much doubt that this disgusting vice has been becoming…more ‘fashionable’…”. The Scotsman took a similar editorial stance, and the Daily Record could barely conceal its outrage. Speaking at the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1958, Adair caused panic in the cloisters by claiming that within weeks of the publication of the Wolfenden Report, a homosexual ‘club’ in London, offering information on meeting places including public lavatories, had received nearly 50 applications for membership, and in one square mile of London there were over 100 male prostitutes offering depraved services. Adair’s fear was that any change in law would enable ‘perverts to practice sin for the sake of sinning’ in Scotland.

Yet, there was an element of mendacity about Adair’s claims. He would have known, first hand, that homosexual prostitution was already thriving in Scotland by the turn of the 20th century and by the 1920s there were organised groups of male prostitutes operating in Glasgow – a city, he had previously hinted, with a a greater attraction for gay men. In reality Adair was upset that the previous policy of ‘silence’ regarding same-sex desire in Scotland was under threat, and by emphasising the potential for moral turpitude, he hoped to consign homosexual law reform in Scotland to the dustbin. In any event this was what effectively happened due to the peculiarities of Scots Law. Adair became a representative, a figurehead, for moral objections to homosexual law reform in Scotland, and would have been quietly satisfied that within a few months of the publication of the Wolfenden Report, Scottish silence had been restored (albeit to be resurrected in the mid 1960s, but with a similar result). Adair, his job done, could retire into relative obscurity, appearing now and again from his home in Pollokshields to offer a talk on old Glasgow, or to attend meetings of The Galloway Association of Glasgow.

Copyright © Jeff Meek 2013

All Rights Reserved.