By the midpoint of the 19th century successful businesses wished to build offices that reflected their optimism, growing wealth and confidence, especially at a time when Glasgow was cementing its position as the second city of the Empire. One such organisation, which emerged during the early part of the century was The National Bank of Scotland (NBS) (established in 1825) and after a failure to acquire the Glasgow and Ship Bank, the NBS undertook to open their first Glasgow branch in 1843. Occupying temporary accommodation in the first instance the bank launched a public competition to design a more suitable building. A young London architect, John Gibson (1817-92), then working under Charles Barry, entered the competition and his plan was unanimously chosen as the winner. On Gibson’s first official trip to the city he was treated to a public dinner given by the ‘principal gentlemen of Glasgow’ and commented that ‘I was much gratified by the kindness shown to me in Glasgow, and surprised to see so many public monuments, and all by the best sculptors’. After the final plans were approved construction of the new building, in Queen Street, began that winter and was completed within 4 years.

According to ‘The Glasgow Tourist and Itinerary’ (1850) the completed building was ‘commodious and elegant; the telling-room being elaborately ornamented, and its polychromatic decorations [executed by H. Bogle & Co., Glasgow, house painters to the Queen] are tasteful and appropriate’. An article in The Civil Engineer and Architect’s Journal in September 1849 confidently stated that ‘there is not yet one building of the class in all the metropolis which offers anything like the same degree and completeness of embellishment’.

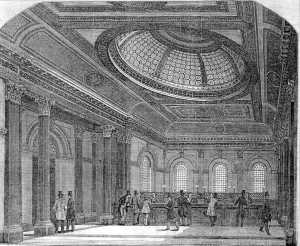

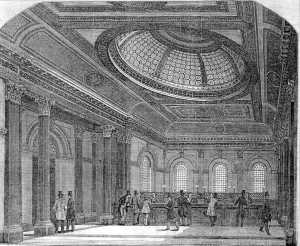

An engraving of the National Bank building, 1849

The exterior of the building was similarly lauded for its beauty. The building’s inspiration was to be found in the work of Vincenzo Scamozzi, the Venetian architect, with the ground floor rusticated with five arched openings, the centre opening housing the doorway. The entrance is flanked by double Ionic columns. The windows are separated by pilasters (flat columns, flush to wall), which appear in double form at the corners of the building. The original door was of a bronze-green colour and was ornamented with bronze paterae (circular ornaments) and studs.

The Telling Room of the Bank

The architectural design of the building was impressive but was further improved by the addition of sculptures designed by London’s John Thomas (1818-62), who was to work often within Glasgow, and worked on the Houses of Parliament, Balmoral, Windsor, and Buckingham Palace, and became a favourite artist of Prince Albert. The Prince commissioned Thomas to create two large bas-reliefs of ‘Peace’ and ‘War’ for the latter palace. Thomas was to create the Graeco-Egyptian Houldsworth Mausoleum at the Necropolis and the designs for the industrialist Houldsworth’s new home at 1 Park Terrace. For the National Bank, Thomas ornamented the windows with carved keystones representing major rivers of Britain (the Clyde, Thames, Tweed, Severn & Humber – although there has been some dispute as to whether the latter two were in fact the Shannon and Wye).

A small bust of Queen Victoria was placed in the centre of the attic frieze. Portland stone Vase finials and the Royal Arms, supported by a unicorn and lion, ornament the roof frontage of the building which was faced with stone with a light-grey tint, supplied by the Binnie Quarries near Edinburgh, and the masonry was executed by John Buchanan. The side of the building was similar in design to the front but had only three windows per floor, divided by double pilasters. The rear of the bank had an out-standing gallery, within which stood another entrance which was ornamented by Ionic columns.

The interior of the building was resplendent with the telling-room of the bank boasting a 23-foot in diameter dome filled with colourful stained glass, provided by Ballantine & Allan of Edinburgh, who had also provided the stained glass for the House of Lords. The walls were decorated with columns and pilasters painted a deep red, with white bases and tops. Near the base of the pilasters a band of black marble framed the flooring. The frieze above the columns was adorned with roses, shamrocks and thistles. The ceiling, following this colourful design, was crimson, blue and gold, with this work being undertaken by the Glasgow firm, Bogle & Co. The floor between telling counters (carved from mahogany), directly beneath the dome, was paved with coloured marbles, which in the centre formed a radiating star. The telling-room was positioned to the rear of the building and the front area was to be found along a handsome corridor, adorned with panels of contrasting colours, which led to a committee room, manager’s room, and waiting room.

So enthralled with the design of the building, The Civil Engineer and Architect’s Journal (1849) enthused that ‘the Scotch seem to have got greatly ahead of us in tasteful as well as liberal decoration of places of public business’. However, such splendour, which had initially excited the Bank’s directors, was to lose its appeal as the 19th century progressed. By 1896 the NBS was seeking new and more suitable premises for its business in Buchanan Street, at the junction of Buchanan Street and St Vincent’s Street. In a letter to architects a representative of the Bank’s directors stated ‘My directors do not favour the idea of anything of the nature of elaborate decoration…and have expressed a leaning towards a thoroughly businesslike building…of chaste design’.

Thus, the future of the building appeared bleak by the tail end of the century. However, efforts were already underway to purchase the building from the NBS. In November 1896 an offer from Mr Richard H. Hunter, philanthropist and chairman of Hunter, Barr & Co Ltd, wholesale warehousemen & shipowners, was accepted on the provision that the Bank could continue to occupy the building for a further 4 years, while their new premises were constructed. However, this initial bid failed, but the same company made another offer in July 1898 to purchase the building for £59,000. The Bank rejected this bid and were holding out for an offer of £60,000, which they received in August the same year with provision to allow the bank to remain in the premises until 1901. Hunter was to retain the land from the sale and on this built the Hunter Barr Building (which still occupies the site today) designed by David Barclay.

From Bank to Public Hall: The Rebirth

One of the problems Glasgow Corporation had faced in supplying a public building for the Langside, Battlefield and Mount Florida districts (promised after annexation) was where to build. After annexation a committee was appointed by the ratepayers of the districts to negotiate with the corporation. After much discussion, bickering and frank exchange of opinions 3 main ‘preferred’ sites were identified: 1. The north side of Battle Place, on the Camphill Estate 2. The south side of Battle Place on ground owned by two proprietors 3. At the junction of Langside Avenue and Pollokshaws Road, also in the grounds of Camphill (the least preferred). Positioning the halls at the place of Queen Mary’s defeat at the Battle of Langside was initially viewed by the corporation as the victory of sentiment over practicality. In 1899 Bailie John Oatts suggested that the south side of Battle Place was the most preferred site but purchasing the ground would prove to be too expensive. The north side was problematic as the elevation of the ground would prove troublesome to builders. The land at the junction of Langside Avenue and Pollokshaws Road was problematic as the position of the new halls would favour the residents of one district. It would appear that the chosen site, the latter of the options, was a compromise.

Yet, the decision met with considerable protest from sections of the local community who took exception on two grounds: the encroachment onto the Camphill grounds & the geographical positioning of the new halls. Indeed, in 1901 a committee of ratepayers took their objections before Sheriff Guthrie and the corporation were accused of being ‘high handed’ while the objectors were accused of ‘humbugging’. Further, the objectors did not believe that the former National Bank building, newly acquired by the corporation, was fit for purpose. The building had not been retained by Hunter after he purchased the site in Queen Street and the offer of a ready-made public hall was too tempting for Glasgow Corporation to dismiss, even if it meant bringing it, brick-by-brick, to the Southside.

Once the lengthy discussions had ceased and legal objections had been rejected Alexander Beith McDonald was instructed to re-design the building’s interior (although the bulk of the work was undertaken by Robert Horn). A utilitarian building was needed so, regrettably, much of lavish interior was removed (the interior had previously been altered under the direction of James Salmon in the mid 1850s). The entrance was given a green-tiled hallway and a double staircase was constructed which led up to the lesser hall (with gallery), which when finished could house 320. The upper hall was designed to accommodate a further 100 souls, while the former telling-room was turned into the large hall, which could accommodate 850. Sadly, the splendid stained glass-filled dome was removed entirely and the plasterwork replaced. A reception room was designed to accommodate around 20 people, and several smaller spaces were created. The new Langside Public Halls were also equipped with cloakrooms, a buffet, and kitchen.

After much delay, deliberation and some dissent, the new halls for Langside were officially opened on the 24 December 1903. The Lord Provost John Ure Primrose, Baronet, was unable to attend due to a prior commitment and his place was taken by Councillor William Martin, the convener of the special committee of halls, Councillor W. F. Anderson and Bailie Finlay. Finlay, acting on behalf of the Watching and Lighting Committee accepted custody of the halls.

Councillor Anderson informed the gathered crowd that the builders who had re-erected the building using the 70,000 numbered stones recovered from the demolished bank building did so without seeking a farthing of profit, which was met with applause. Those attending the opening were treated to vocal and orchestral concert. This grand opening was covered by the Glasgow Herald and The Scotsman newspapers, amongst others, in their Christmas Day 1903 editions.

Over the past century Langside Public Halls have played a significant role in the south Glasgow community. The halls have figured prominently in the rich and diverse social and political history of the city, playing host to John Mclean and the famous Red Clydesiders (Maclean was arrested 4 times outside the halls), Sylvia Pankhurst and the Scottish branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union, and the Scottish Young Conservatives annual conference. It has been a true community hall where Glasgow Progressive Synagogue was temporarily based, where the annual Glasgow Congress ‘International’ chess event packed out the main halls, where the world famous Smetana Quartet of Prague performed in concert, and where the resident band The Crackerjacks filled the floor of the large hall in the 1950s.

John Maclean

The story of Langside Public Halls is a truly remarkable one. It is a story of architectural excellence and a story of survival. With the removal of the National Bank of Scotland, Queen Street Office to the southside of the city one of Glasgow’s most admired buildings survived to play a central role in the social and community history of the area.

Copyright © Jeff Meek 2013

All Rights Reserved.